Lately I’ve discovered sentiment analysis that combines natural language processing with text analysis to basically identify (and quantify!) feelings created by words. Some R packages like the syuzhet package are now available from the CRAN and doing your very own natural language analysis has never been so easy.

Besides R packages, you will most certainly need some texts to analyze. For those of you who never heard about it, I would highly suggest having a look at the Project Gutenberg. The Project Gutenberg currently offers over 50,000 free eBooks you are allowed to download because their copyrights have expired.

Personally, I’m a huge fan of Edgar Allan Poe and in his works exhaustive descriptions of a variety of emotions are quite common. So his novels should represent really good data to analyze. Even better, there are so many different novels and we certainly can try to compare them. After all, I usually read late and I might want to choose wisely the novel so as to be able to sleep afterwards.

How to download texts using a Unix shell

For the purpose of this work, I’m using the plain text UTF-8 files available via the the Project Gutenberg website. A very convenient way to retrieve them is to use the terminal.

# This is Unix code

cd ~/path/to/directory

curl URLtoTransfer > text.txtThe complete works of Edgar Allan Poe I used is available here.

Let’s first get the data ready for analysis

Having the Edgar Allan Poe texts in a working directory, it’s fast and easy to read them using the read_lines command from the readr package. The Project Gutenberg has header and footer information we do not need. Using skip and n_max options allows leaving them out and import only the novels.

# Import the first volume

library(readr)

rawtext <- read_lines("../data/poeVol1.txt", skip = 956, n_max = 7902)Well, now let’s use the R’s syuzhet package to break down sentence-by-sentence and the package’s get_sentiment function to quantify positive and negative sentiments. At the same time, we certainly want to make sure we get rid of all these annoying \n newline marks in the text. I’m not sure if and how they could affect the quantification, but better safe than sorry.

# Break down sentence by sentence, remove '\n' and get sentiment

library(syuzhet)

sentences <- get_sentences(rawtext)

poeVol1 <- gsub("\n", " ", sentences)

sentiment <- get_sentiment(poeVol1)The get_sentiment function can use several methods to analyze the text. The default method, "syuzhet" is a custom sentiment dictionary developed in the Nebraska Literary Lab. According to them, the default dictionary should “be better tuned to fiction as the terms were extracted from a collection of 165,000 human coded sentences taken from a small corpus of contemporary novels.”

Okay, Edgar Allan Poe novels might be over one hundred years old, which makes them I guess not really contemporary, but at least they’re composed of fictional work only. Additionally, Julia Silge used the same method on her blog, where she mined her favorite book, Pride and Prejudice. Have a look: it’s a fantastic (and very inspiring) example!

That sentimental feeling

Now that we broke down sentence by sentence and cleaned the text, how about having a look at some examples. To avoid any bias – after all you have no reason to trust me – you can generate them randomly.

# Randomly select three sentences in the text

rn <- sample(length(poeVol1), 3)I did it that way and obtained 1657, 1225, and 3232, which I have to set manually for the purpose of this post. But please feel free to experiment should you really not trust me at all!

So, trying to get sentiment for the first one:

poeVol1[rn[1]]

## [1] "By this time the cries had ceased; but, as the party rushed up the first flight of stairs, two or more rough voices in angry contention were distinguished and seemed to proceed from the upper part of the house."

get_nrc_sentiment(poeVol1[rn[1]])

## anger anticipation disgust fear joy sadness surprise trust negative

## 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

## positive

## 1 0Well, it gives a pretty good result! There is definitively some anger, anticipation and disgust in that sentence. The overall felling is most certainly negative. Just imagine yourself during the 19th century, in the middle of a lovely diner at your aunt’s mansion, just about to savor a filet de sole à la Dugléré, interrupted by some cries, having to rush upstairs without any time to warm-up. Indeed very negative!

Another one:

poeVol1[rn[2]]

## [1] "You will observe that the stories told are all about money-seekers, not about money-finders."

get_nrc_sentiment(poeVol1[rn[2]])

## anger anticipation disgust fear joy sadness surprise trust negative

## 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

## positive

## 1 1Hmm, this one is not an easy one and the result is maybe less convincing here. Anyway, with a little imagination one can identify some of the feelings recognized. And there is definitively neither disgust or fear, nor sadness or surprise in that sentence. I guess overall it’s slightly positive as well. After all the money-seekers could eventually become money-finders some day!

Okay, last one:

poeVol1[rn[3]]

## [1] "Mem:_ at 25,000 feet elevation the sky appears nearly black, and the stars are distinctly visible; while the sea does not seem convex (as one might suppose) but absolutely and most unequivocally _concave_.(*1) \"_Monday, the 8th_."

get_nrc_sentiment(poeVol1[rn[3]])

## anger anticipation disgust fear joy sadness surprise trust negative

## 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1

## positive

## 1 4I do not particularly suffer from acrophobia, but back in the 19th century, 25,000 feet elevation was pretty unusual and certainly a bit frightening. There is some disappointment associated to the shape of the sea. After spending so many years at school, I also expected it to be rather convex. But anyway, under the visible stars the view is certainly awesome and as long the as the aerostat works fine, everything should be just fine. So definitively positive too!

Break down novel by novel

So far so good. But my primarily idea was to compare feelings among novels. Now that we have code to extract the sentiment, we need to delimit each narrative. The first volume of Edgar Allan Poe works contains eight of them. Names can be found in the Project Gutenberg’s header and we will create a list to automatically search for them among the text with regular expressions.

novels <- c("The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaall", "The Gold-Bug",

"Four Beasts in One--The Homo-Cameleopard", "The Murders in the Rue Morgue",

"The Mystery of Marie Roget", "The Balloon-Hoax",

"MS Found in a Bottle", "The Oval Portrait")Let’s create a dataframe that contains sentence number and sentiment through the whole text.

# Create dataframe with sentence number and sentiment

poenrcVol1 <- cbind(sentence = seq_along(sentences), get_nrc_sentiment(poeVol1))

poenrcVol1$sentiment <- sentimentFollowing loop will make a novel vector for the dataframe and name each novel.

# Search for novel in the text and name each of them

poenrcVol1$novel <- NA

for(i in 1:length(novels)) {

while(i <= length(novels)) {

poenrcVol1[grep(toupper(novels[i]), sentences)[1]:length(sentences), 'novel'] <- novels[i]

i = i+1

}

}While the following one will restart the line number count at the beginning of each novel.

# Restart the linenumber count at the beginning of each novel

poenrcVol1$novel <- as.factor(poenrcVol1$novel)

for(i in 1:length(novels)) {

while(i <= length(novels)) {

poenrcVol1$sentence[poenrcVol1$novel == novels[i]] <- seq_along(sentences)

i = i+1

}

}Time for some plots

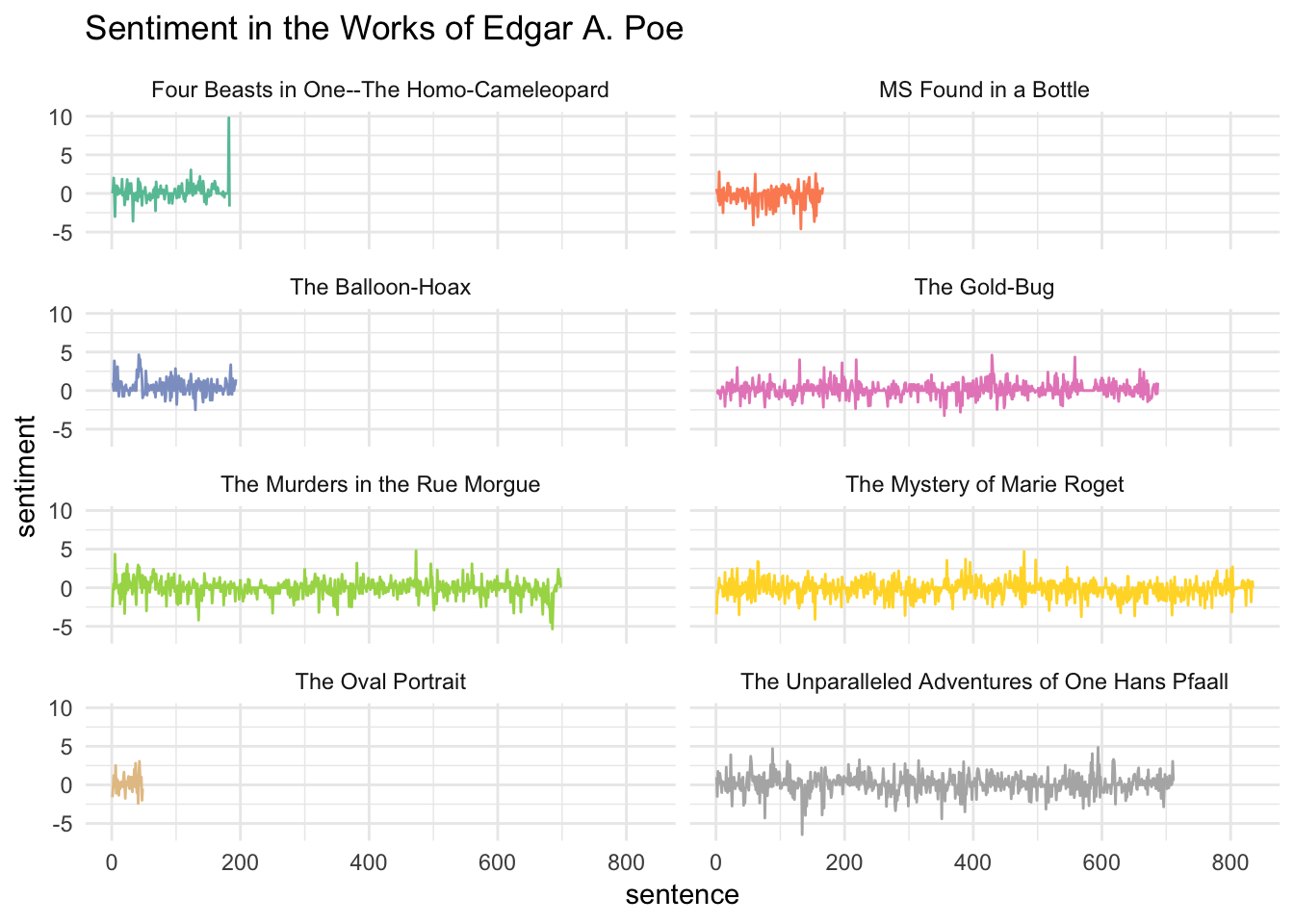

The overall positive vs. negative sentiment in the novels of Edgar Allan Poe can now be roughly plotted.

library(ggplot2)

library(RColorBrewer)

ggplot(poenrcVol1, aes(x = sentence, y = sentiment, color = novel)) +

geom_line() +

facet_wrap(~novel, nrow = 4, ncol = 2) +

ggtitle(expression(paste("Sentiment in the Works of Edgar A. Poe"))) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_colour_brewer(palette = "Set2") +

theme(legend.position = "none")

It definitively happens a lot in these novels. However, it is not particularly easy to read and they all have different lengths, which makes them hard to compare. In addition, we only represented the overall positive vs. negative sentiment there.

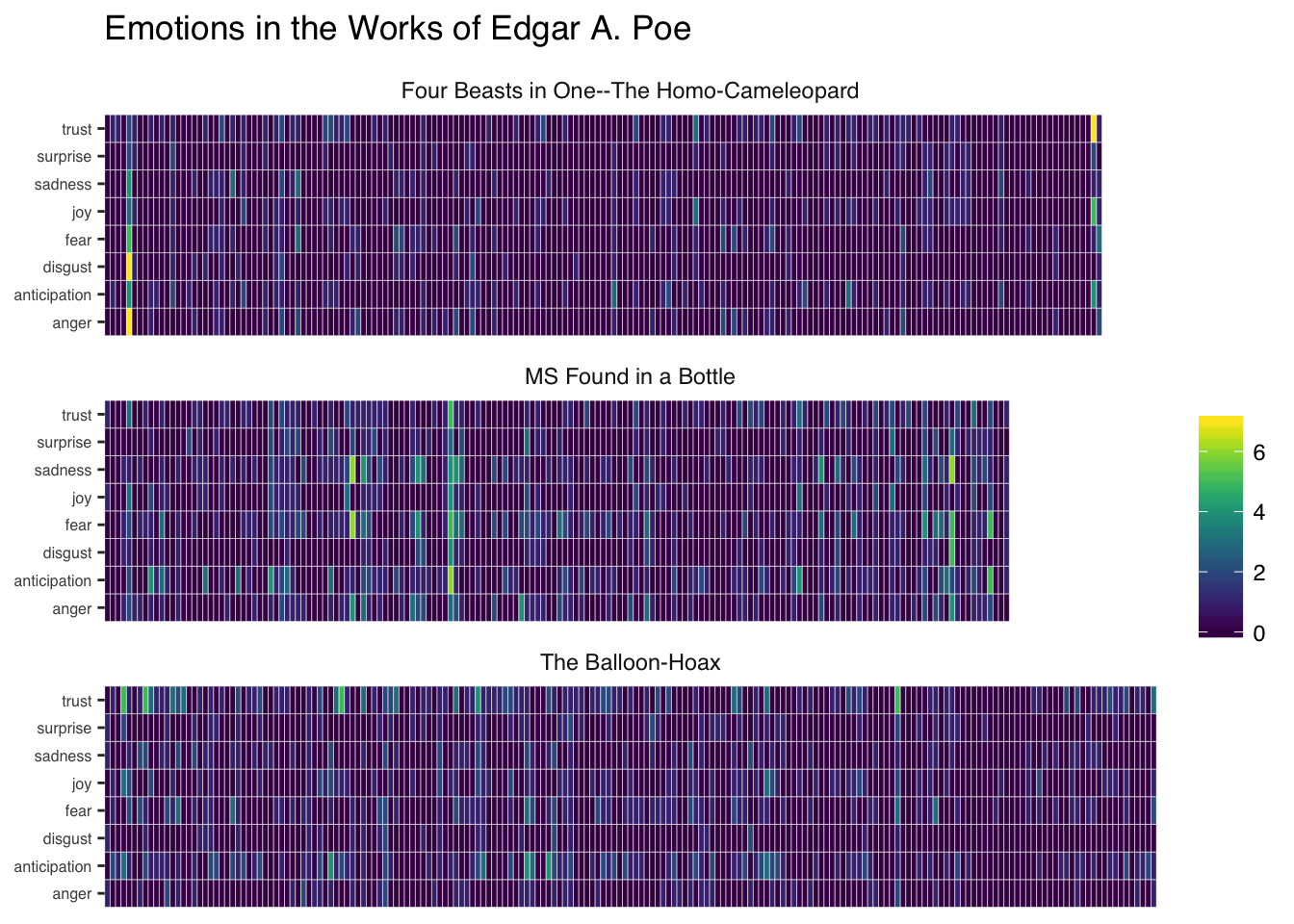

Plotting all emotions within one figure is possible with a heatmap. But before we can do that, we have to reorganize a bit our data. So let’s create a new dataframe melting all emotions per sentence and novel and rename the columns.

# Create reorganized dataframe

emotions <- poenrcVol1 %>%

select(sentence, novel, anger, anticipation, disgust,

fear, joy, sadness, surprise, trust) %>%

melt(id = c("sentence", "novel"))

# Rename columns

colnames(emotions) <- c("sentence", "novel", "sentiment", "value")And here we go.

library(ggthemes)

library(viridis)

# Just three of them, about the same length

ggplot(emotions[which(emotions$novel %in%

c("The Balloon-Hoax",

"Four Beasts in One--The Homo-Cameleopard",

"MS Found in a Bottle")),],

aes(x = sentence, y = sentiment, fill = value)) +

geom_tile(color = "white", size = 0.1) +

facet_wrap(~novel, nrow = 3) +

scale_fill_viridis(name = "") +

theme_tufte(base_family = "Helvetica") +

labs(x = NULL, y = NULL,

title = expression(paste("Emotions in the Works of Edgar A. Poe"))) +

scale_x_discrete(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme(axis.text = element_text(size = 6)) +

theme(legend.title = element_text(size = 8))

Again, it is not really perfect. But somehow, we have a better idea of what happens in the text and when. But we didn’t resolve the length difference issue. Besides, we now have to deal with even more information, which makes the quick comparison among novels harder.

And now for something completely different

Following the very same steps, it’s relatively easy to extract sentiment of all Edgar Allan Poe novels from the four other volumes (all available from Gutenberg: Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, and Volume 5).

After that we can create a new dataframe combining values of all novels.

# Create a new big dataframe

df <- rbind.data.frame(poenrcVol1, poenrcVol2, poenrcVol3, poenrcVol4, poenrcVol5)

head(unique(df$novel), n = 5)

## [1] The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaall

## [2] The Gold-Bug

## [3] Four Beasts in One--The Homo-Cameleopard

## [4] The Murders in the Rue Morgue

## [5] The Mystery of Marie Roget

## 65 Levels: Four Beasts in One--The Homo-Cameleopard ...By now, we manage to get the sentiment out of 65 Edgar Allan Poe novels. Nice! I wasn’t able to localize a few of them, which were mentioned in the header but didn’t pop-up in the text. Anyway, 65 is enough to run a principal component analysis. All we have to do is to reorganize our dataframe to get the mean for each emotion. That way, we get rid of the length issue. It is surely not perfectly standardized and the shortest novels might be disadvantaged, but it’s worth a try.

# Create a reorganized version of our dataframe

library(plyr)

dfnew <- ddply(df, .(novel), summarise,

anger = mean(anger),

anticipation = mean(anticipation),

disgust = mean(disgust),

fear = mean(fear),

joy = mean(joy),

sadness = mean(sadness),

surprise = mean(surprise),

trust = mean(trust),

sentiment = mean(sentiment),

negative = mean(negative),

positive = mean(positive))

# Name row (and remove novel from dataframe)

rownames(dfnew) <- dfnew$novel; dfnew$novel <- NULLLet’s run the PCA and have a look at the components.

# Run the PCA and summarize components

df.pca <- prcomp(dfnew[,1:8], center = TRUE, scale = TRUE)

summary(df.pca)

## Importance of components:

## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6

## Standard deviation 2.265 1.3699 0.57000 0.49109 0.44609 0.30879

## Proportion of Variance 0.641 0.2346 0.04061 0.03015 0.02487 0.01192

## Cumulative Proportion 0.641 0.8756 0.91623 0.94637 0.97125 0.98317

## PC7 PC8

## Standard deviation 0.30177 0.20880

## Proportion of Variance 0.01138 0.00545

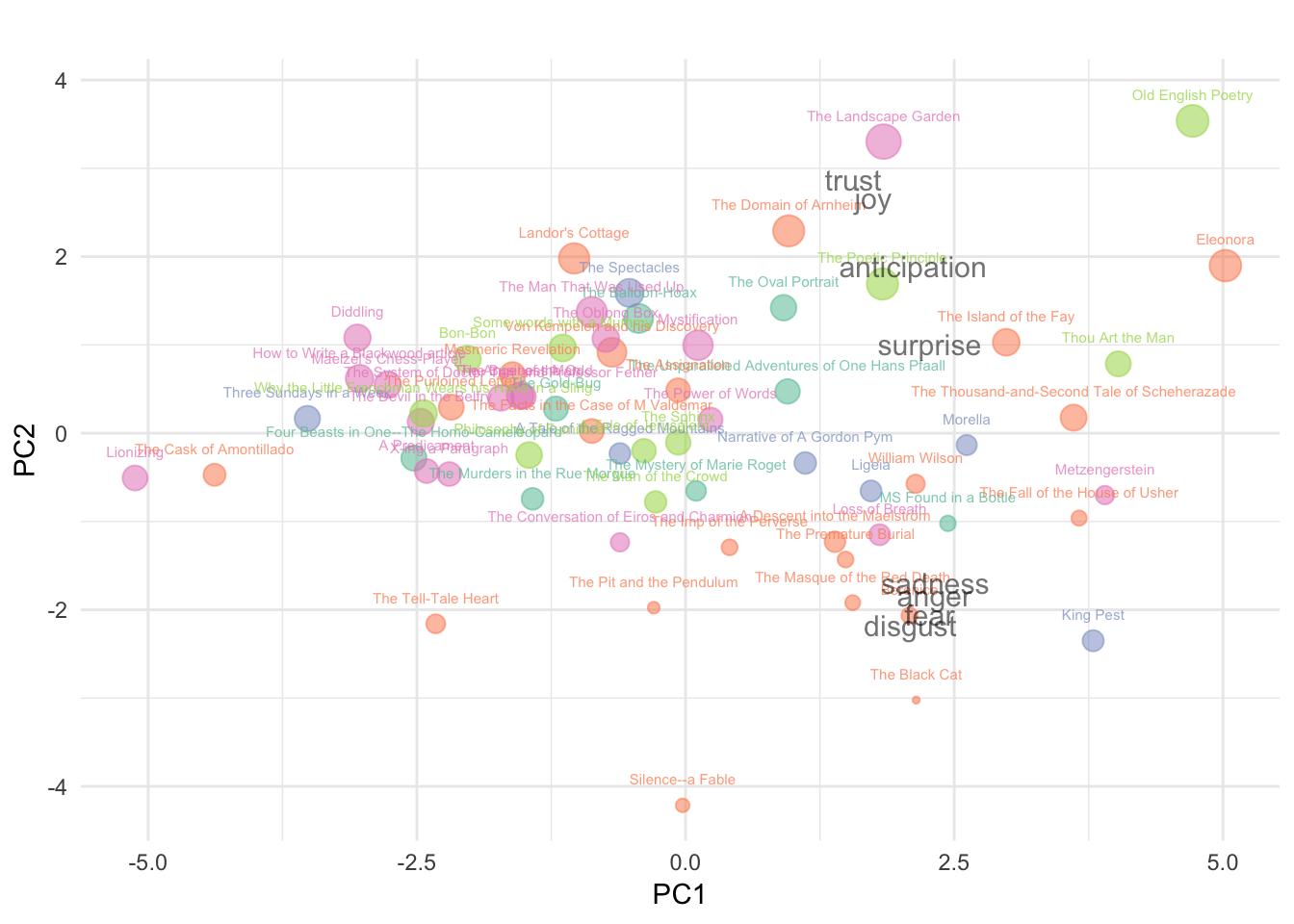

## Cumulative Proportion 0.99455 1.00000Great! The two first components explain almost 90% of the variance. Having a second through on that, it was pretty obvious. Some novels are really emotional, whereas others aren’t that much. The first component of the PCA largely reflects that emotional scale. In addition, emotions quantified can be roughly split into two groups: more positive ones (i.e., joy, trust, surprise, and anticipation) and more negative ones (i.e., sadness, anger, fear, and disgust). The second component of the PCA separates indeed pretty well more positive novels from more negative ones.

But enough explanation, we now have only two dimensions left, which is perfectly suited for a nice plot. Before that, we might want to add a vector to indicate us the volume from which the novel was initially extracted and create some more dataframes containing other information we will need to nicely plot the data.

# Add the volume number

dfnew$volume <- ifelse(row.names(dfnew) %in% poenrcVol1$novel, "Volume 1",

ifelse(row.names(dfnew) %in% poenrcVol2$novel, "Volume 2",

ifelse(row.names(dfnew) %in% poenrcVol3$novel, "Volume 3",

ifelse(row.names(dfnew) %in% poenrcVol4$novel, "Volume 4",

ifelse(row.names(dfnew) %in% poenrcVol5$novel, "Volume 5", NA)))))

# Create the scores dataframe

scores <- data.frame(dfnew, df.pca$x)

# Calculate legend coordinates

datapc <- data.frame(df.pca$rotation)

mult <- min(

(max(scores$PC2) - min(scores$PC2)/(max(datapc$PC2)-min(datapc$PC2))),

(max(scores$PC1) - min(scores$PC1)/(max(datapc$PC1)-min(datapc$PC1))))

datapc <- transform(datapc,

v1 = .7 * mult * (get("PC1")),

v2 = .7 * mult * (get("PC2")))And finally…

qplot(data = scores, x = PC1, y = PC2, size = 1+sentiment, colour = volume, alpha = 0.1) +

geom_text(alpha = .75, size = 2, aes(label = row.names(df.pca$x)), nudge_y = .3) +

ggtitle("") +

xlab("PC1") +

ylab("PC2") +

theme_minimal() +

scale_colour_brewer(palette = "Set2") +

theme(legend.position = "none") +

theme(legend.title = element_blank()) +

geom_text(data = datapc, aes(x = v1, y = v2, label = rownames(df.pca$rotation)),

size = 4, vjust = 1, color = "black")

And there it’s! We can now easily see the differences between all novels. Left to the right they become more emotional. Besides, the more positive ones cluster at the top-right corner, whereas the more negative ones cluster at the bottom-right corner. Without any surprise, reading “The Landscape Garden”, “Old English Poetry”, or “The Poetic Principle” before sleeping seems a much wiser choice than reading “King Pest”, “The Masque of the Red Death”, or “The Black Cat”. That’s very sad, because I guess the later is one of my favorite!

Colors are function of the complete work volume from which the novels were extracted. One can see that the “Orange” volume (the second) is extremely heterogeneous and contains more of the most negative novels, whereas “Pink” and “Green” (volume 4 and 5, respectively) contain the most positive ones. Moreover, “Cyan” (volume 1) is relatively homogeneous and concentrates around the middle. I’m not totally sure if this complete edition was established in a chronological order, but it could be interesting to have a look at Edgar Allan Poe’s life and career.

What’s next

Well, I most certainly want to double-check the results. I found the difference between the complete work volumes very interesting. I really would like to know if this difference is a real one and if yes: how to possibly explain it. In addition, Poe’s novels are commonly categorized into “Adventure”, “Humor”, “Horror”, etc. It could represent a way to quickly and roughly compare them. In adventure or humor tales, we rather expect a happy ending. In horror stories on the contrary, not so much. Focusing only on the end of each novel could be another rational approach. I guess I could also simply spend some evenings reading them again.